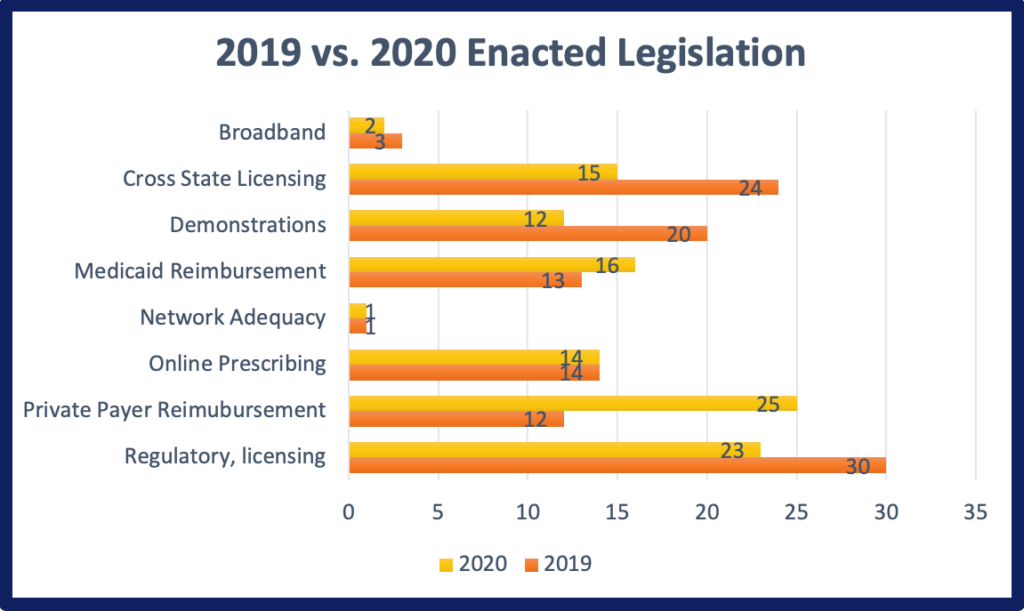

2020 has been an unprecedented year for telehealth. Spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth has become a common form of healthcare delivery over the past year. In no small part, expanded reimbursement and professional practice policies has enabled this transformation. Among 36 states, 104 legislative bills passed in the 2019 legislative session. This was relatively consistent with 2019, when 113 bills were enacted. However, the topics that were addressed were significantly different in 2020. For example, bills either creating or making modifications to laws related to private payers shot up from 12 bills in 2019 to 25 bills in 2020. Likewise, there was also a slight increase in Medicaid reimbursement enacted legislation as well. On the other side, there was a decrease in bills related to pilots, demonstrations and grants as well as cross state licensing legislation. These variations between 2019 and 2020 were most likely due to the need for more expansive telehealth policies on a large scale, rather than confining telehealth flexibilities to pilot projects or demonstrations. The drop in cross state licensing legislation, more than likely occurred because during the pandemic most states implemented licensing waivers allowing for out-of-state practice. Therefore, addressing cross state licensing needs through legislation may not have been at the forefront of minds, while there were more pressing concerns. Thirty-five of the 104 bills were in direct response or explicitly mentioned the COVID-19 public health emergency. CCHP’s 2020 roundup of state approved legislation which includes a detailed listing of all bills by topic area and state is now available.

MEDICAID

While all states already provide some type of reimbursement for telehealth delivered services in Medicaid, there was still a good amount of telehealth legislation focused on broadening Medicaid policies and reducing barriers to the use of telehealth. For example, Louisiana Medicaid is now obligated to have comparable telehealth reimbursement policies to Medicare, according to newly passed bill HB 589. Previously, there was no law obligating Medicaid to cover telehealth at all in Louisiana. Maine passed another bill (LD 1974) requiring Medicaid reimbursement for case management services delivered through telehealth to targeted populations. Expanding the modalities that can be used to deliver care beyond live video was also something noted in a few states. For example, Michigan HB 5415 now requires its Medicaid program to provide coverage for remote patient monitoring services. New York was one of the few states to permanently address the use of telephone in Medicaid, a measure most states have taken on a temporary basis during the pandemic, but not addressed in permanent policy. New York’s SB 8416 adds audio-only to the definition of telehealth that applies to Medicaid. Expanding allowable originating site settings was another common policy expansion made in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE). For example, Michigan also passed a bill (HB 5416) requiring Medicaid to cover telehealth when patients are at home or a school-based setting.

PRIVATE PAYER

Private payer laws were the category that saw the largest jump in the number of bills between 2019 and 2020. Although only one state (West Virginia – HB 4003) added a new telehealth private payer law, other states took steps to strengthen and/or modify their laws. For example, Utah HB 313 requires that private payers provide coverage of the telemedicine services that are covered by Medicare for network providers and reimburse at a commercially reasonable rate. Washington SB 5385 strengthened their law by providing explicit payment parity, requiring a health plan to “reimburse a provider for a health care service provided to a covered person through telemedicine at the same rate as if the health service was provided in person by the provider”. It does, however, go on to specify that hospitals, hospital systems, telemedicine companies and provider groups consisting of eleven or more providers may elect to negotiate a reimbursement rate for telemedicine services different from the rate of in-person. It also removes the requirement that if the service is provided by store-and-forward that there be an associated office visit.

Louisiana HB 530 addressed reimbursement of remote patient monitoring, and specifies certain requirements that must be met for a provider to receive reimbursement for RPM, such as assessing and monitoring clinical data, detecting changes in condition based on telemedicine or telehealth encounters and implementing a management plan. It also requires that health insurers conspicuously display on their website information regarding their telehealth services and remote patient monitoring services. This is similar to a Texas law passed in 2017 which also requires insurers to conspicuously display on their websites their telehealth policies.

Maryland also passed telehealth bills (HB 1208/SB 502) which specifies explicitly that mental health care services provided to a patient’s home setting falls under the definition of telehealth and that insurers must provide reimbursement for substance use disorder. Iowa also passed a telehealth private payer bill (SF 2261) specifically aimed at schools, requiring that an insurer not deny coverage for behavioral health services provided via telehealth solely because the services are delivered in a school.

CROSS STATE LICENSING

As was the case in 2019, a large proportion of the bills related to cross state licensing were states enacting one of five interstate licensure compacts for out-of-state licensed providers to practice in other Compact states under certain circumstances. Each Compact operates differently with the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact being an expedited licensure process that requires physicians to still submit separate applications and fees to each Compact state they wish to provide services in. The following is a recap of the progress each Compact made in 2020:

• The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC) – The IMLC Compact currently stands at 29 states, DC and Guam participating. No new states joined in 2020. Both Wisconsin and Arizona asked to withdraw from the Compact in 2019, however they are still listed as active members on the IMLC website.

• The Nurses Licensure Compact (NLC) – The NLC Compact currently stands at 34 states participating. No new states joined in 2020.

• Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology Interstate Compact (ASLP-IC) – The ASLP-IC currently stands at 7 states participating. Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming all joined the Compact within the 2020 legislative session.

• The Physical Therapy Compact (PTC) – The PTC currently stands at 28 states. South Dakota and Wisconsin joined within the 2020 legislative session

• The Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact currently stands at 15 states. North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Virginia joined within the 2020 legislative session. The Compact in North Carolina and Virginia does not go into effect until 2021.

DEMONSTRATIONS, PILOTS & STUDIES

2020 still saw its fair share of legislation focused on demonstrations, pilots and/or studies. However, while 2019 pilots primarily focused on mental health or substance use disorder, the vast majority of 2020 enacted legislation were intended to test the efficacy of telehealth or gather data, often in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic or delivery of emergency services. One such bill was Oregon HB 4212 which requires providers to collect encounter data on race, ethnicity and language for encounters that occur, whether performed in-person or via telemedicine, for purposes of providing health care services related to COVID-19, including but not limited to ordering or performing COVID tests. The data collected in Oregon will undoubtedly be used in future studies to determine whether patients of all races, ethnicities and languages receive a high standard of care. Likewise, Mississippi’s SB 2311 also allows the State Board of Health to promulgate rules and collect data on the use of telemedicine and electronic health records to deliver telemedicine services.

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE & PRESCRIBING

A number of states refined definitions of telemedicine/telehealth within specific professions. For example, Virginia SB 122 defined teledentistry, and Colorado HB 1230 defines telehealth for occupational therapy. A few states also broadened their definitions of telehealth, including Idaho with H 342 which refined their definition of telehealth services in their Telehealth Access Act to include synchronous or asynchronous communication methods, remote monitoring, transfer of medical data, health-related education, public health services and health administration. In some cases, legislation included requirements for establishing the provider-patient relationship and prescribing. For example, Maryland companion bills HB 448 and SB 402 authorize practitioners to establish a practitioner-patient relationship through telehealth under certain circumstances. It also requires health care practitioners to be held to the same standards of practice as in-person health care settings, to perform a clinical evaluation before providing treatment or issuing prescriptions through telehealth, to be subject to certain laws when prescribing a controlled substance through telehealth, and to document information in a patient’s medical record.

Finally, Washington passed a unique piece of legislation, SB 6061, which requires that beginning January 1, 2021, a health care professional who provides clinical services through telemedicine, other than a physician or osteopathic physician, must complete a telemedicine training. They are the first state to require a telehealth specific training in order for professionals to utilize telehealth within their state.

COVID-19 PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY SPECIFIC BILLS

Thirty-four percent of bills that passed in 2020 were directly related to the COVID-19 pandemic. These bills directly referenced either COVID-19 or the public health emergency within their text. The bills spanned the categories previously discussed above, from Medicaid to private payers, pilot projects and professional regulation. All COVID-19 related bills took steps to expand the use of telehealth in some way or waive requirements to make it easier for patients and providers to utilize telehealth to deliver or receive care. New Jersey S 2467, for example, extends the duration of certain laws related to COVID-19 which require reimbursement by Medicaid and private payers for telehealth and telemedicine during the COVID emergency. Kentucky’s SB 150, relaxes standard of care requirements and provider-patient relationship during COVID and expires at the end of state of emergency. Similarly, Vermont, H 960 allows for the provision of telemedicine or store-and-forward until March 31, 2021 without complying with certain provisions in certain circumstances. A number of legislatures required demonstrations, pilots and studies also directly involved the COVID-19 experience, including Pennsylvania SB 841, which requires a Disaster Emergency Report that would, among other things, examine data points on increased costs related to provider and staff training, including training on pandemic preparedness and the use of telemedicine. Vermont HB 966, establishes the COVID-RESPONSE Accelerated Broadband Connectivity Program with the purpose of increasing telehealth connectivity during the public health emergency.

Even bills that didn’t mention the COVID-19 PHE explicitly, were certainly influenced or connected to the pandemic. For example, Connecticut’s HB 6001, didn’t explicitly mention COVID-19 or the public health emergency, but because many of the sections of the bill expire on March 21, 2021, it was undoubtedly precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This bill strengthens Connecticut’s private payer law requiring that payers cannot restrict coverage to a specific telehealth platform and places requirements on prescribing using telehealth.

LOOKING AHEAD

2021 promises to be another active year in telehealth policy. With the pandemic expected to persist into early 2021, and then the aftermath likely lingering into the end of year, we expect to continue to see telehealth legislation that addresses the temporary COVID PHE policies, and make some of them permanent. This is critical as many of the waivers and expansions in telehealth policy that have occurred in 2020 are expected to expire at some point in 2021. In 2020 states and even private payers appear to be taking their cues from Medicare and requiring that at the very least payers cover the services Medicare reimburses under the same conditions. With more restrictive Medicare policies expected to go back into effect (unless federal legislation is enacted to change it), including limitations on the geographic location and restrictions around the home as an eligible site, it will be interesting to see if this trend continues. Legislation addressing how audio-only, asynchronous and remote patient monitoring service delivery can be reimbursed is also expected to continue, as those are details often excluded from telehealth bills in previous years, which often only addressed live video service delivery. A lot will most likely also be contingent on the data collected related to the expanded use of telehealth during the PHE and whether or not researchers determine that telehealth has been effective at delivering quality care.