If you’d talked to Brandon Welch in 2013, he probably wouldn’t have expected to be the CEO of a global leader in telemedicine.

Back then, Welch was a University of Utah doctoral student working on a hospital study to make prenatal checkups easier for pregnant women. Virtual visits made sense, but existing HIPAA-compliant platforms were complicated and expensive, so he built his own technology—just for the project.

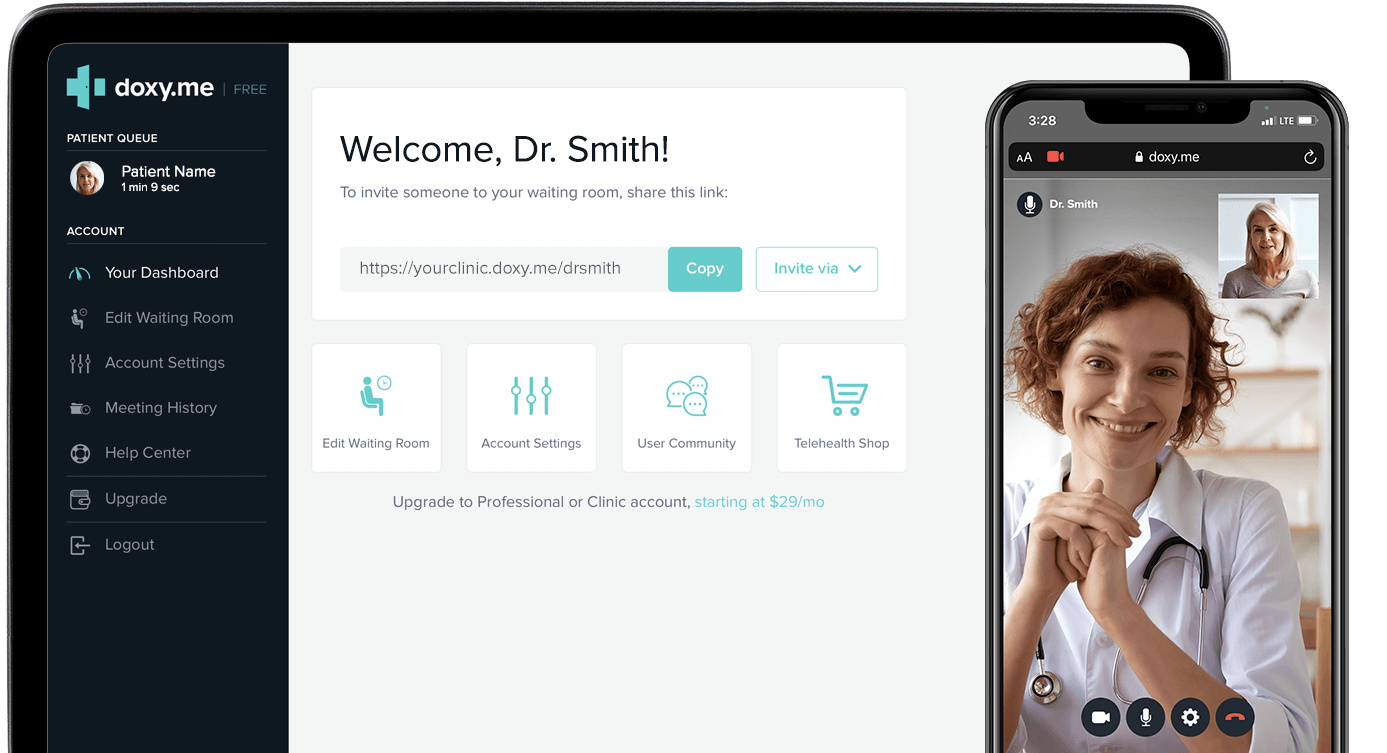

That led to use in a few more telehealth studies and to the launch of Doxy.me, a startup that offered a basic, secure platform for telehealth visits and a paid version with more features. The business grew through word of mouth, but it wasn’t intended to be a huge moneymaker. At one point, Welch took another job as a professor at the Medical University of South Carolina, while his co-founder Dylan Turner couch-surfed and worked in Salt Lake City coffee shops until the business paid his salary.

The pandemic created a rush for telehealth services

As you might have guessed, COVID-19 changed everything. Virtually overnight, doctors across the globe scrambled to figure out how to see patients remotely. Today, Doxy.me owns 30 percent of telehealth market share and has revenues in excess of $50 million. But this kind of fast growth was like walking a tightrope. “It was controlled chaos there,” says Welch. “And there were some white-knuckled moments.”

That was the case for many of Utah’s healthcare providers, its small number of telehealth platforms, and the state’s desperate patients. The number of telehealth medical claims in the state jumped 9,614 percent between December 2019 and December 2020, according to the nonprofit FAIR Health. Utahns mostly flocked to the web to see doctors and therapists for mental health, physical therapy, and specialists for respiratory, heart, and soft-tissue diseases.

“We’ve gone from telehealth being a novelty to being an accepted manner of care,” says Kerry Palakanis, director for ConnectCare, the telehealth arm of Intermountain Healthcare. Intermountain pioneered this telehealth platform in 2015 and saw its telemedicine appointments double early in the pandemic. “We were ready,” she says.

Welch, however, was caught off-guard by the sudden demand. Doxy.me had grown to 89,000 users in its first seven years. So on March 1, 2020, Welch was surprised when 100 providers signed up for the service— five times more than normal. He figured it was a fluke, but a friend in the United Kingdom warned Welch that this COVID thing might be a big deal. “We said, no that’s not going to be anything,” Welch recalls.

By the week’s end, Welch realized it was indeed a huge deal. By that point, 600 to 700 providers were signing up per day. The Doxy.me team jumped into action adding three new servers and automated bots to answer customers’ questions. They paused live onboarding sessions and created a YouTube video explaining the platform for new signups. “We used hundreds of support requests to refine the support and answer questions on our website,” Welch says.

Two weeks in, 5,000 people signed up in one day. The next day, 10,000 people signed up. The next day, 20,000 people. Two months into nationwide lockdown, Doxy.me ballooned to 600,000 providers and nearly 1 million sessions a day—up from the pre-pandemic base of 80,000 users and 12,000 daily sessions.

The fast growth blew Welch’s mind, and though it was a blessing, he knew if not handled properly it could crush the company. Doxy.me aggressively recruited at its Salt Lake and Charleston, S.C. offices, ramping up to 120 people from 10 employees the past year.

In those first few months of the pandemic, new recruits—some of these hires had been previously laid off from the restaurant business—holed up in Welch’s living room, building software, fixing bugs and answering support questions, working 12-hour shifts, stopping for dinner, then returning to work from 9 pm to 1 am.

Soon, Welch’s original pursuit of simplicity and easy access to telehealth became a magnet to providers everywhere. Other telehealth platforms might require weeks or months of onboarding before doctors or clinics could start seeing patients online, and video platforms like Zoom weren’t encrypted end-to-end. Doxy.me uses no computer in the middle to transfer information. The site doesn’t collect data and users are anonymous.

About half of Doxy.me’s users subscribed to the free version, which provided a basic room for a doctor and patient. The paid plans offered more perks, such as analytics, branding, billing, multiple rooms, and more. Suddenly, massive hospital networks with thousands of doctors wanted Doxy.me, and the team quickly created a new plan and features that could accommodate them, and also added seven more servers and built a chatbot to more quickly move people through virtual waiting rooms and into doctors’ “examination rooms.”

The pandemic created demand for (and destigmatized) virtual therapy

While Welch scrambled to deliver on the hospitals and clinic front, entrepreneur Dallen Allred felt a similar surge in visits to his mental health startup Tava Health.

Allred and his wife Cami started Tava Health in 2019 to create a platform that employers could tap so workers could see a therapist or psychiatrist virtually. The couple recognized that Utah ranks among the worst in the US for access to mental health care. In some parts of Utah, patients must drive an hour just to get to a clinic, yet as many as 25.5 percent of the population struggles with mental illness.

Tava’s January 2020 launch proved to be perfect timing. Last summer, 40 percent of US adults reported struggling with mental health or substance abuse, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Virtual visits on Tava Health doubled during its first year of 2020. Yet before the pandemic, doctors and therapists resisted the idea of telehealth for fear of missing the subtle body language cues of patients when face-to-face.

That mindset immediately changed with COVID and has been reinforced ever since. According to Allred, mental health patient outcomes are actually better with telehealth. When a person can meet on their phone or laptop, it takes away the hassle and challenges of attending appointments. No-show rates dropped to five percent with virtual visits, compared to the average 30 percent, he says.

Buoyed by $3 million from investors, Tava Health plans to expand beyond its 100 paying employers this year—most of which are in Utah—and its 100 therapists licensed in 45 states.

Despite the new interest in virtual doctor visits, the sector still faces challenges ahead. The pandemic forced the federal government to fan the flames of telehealth by reducing telehealth regulations, which limited who could be seen, where, for what, and at what cost. Yet those waivers expire at the year’s end.

Now there’s talk of returning to many of the original restrictions on which kinds of visits are eligible and which kinds of patients can tune in remotely.

And insurers, too, may be more inclined to roll back some of their initial pandemic generosity, which included waiving copays and covering more types of virtual visits. In some cases, doctors were getting paid the same amount for virtual visits as they were for in-person visits—which had previously been a barrier to the adoption of telehealth. SelectHealth, Utah’s largest health plan, is already rethinking benefits, reimbursement rates, and planning for stricter criteria on what qualifies for telehealth.

When it comes to mental health, Utah still has regulatory barriers that will limit virtual appointments. Utah is among many states that still bar out-of-state therapists from providing mental health care to its citizens without going through a cumbersome and expensive licensure process. Yet the state lacks the therapists to meet demand. “It’s a stupid law, and it’s outdated,” says Allred.

Therapists also get paid 20 percent to 30 percent less for virtual visits than they do in-person visits. “There is very little that you can’t do well virtually when it comes to mental health,” Allred says. “You’re not listening to a heartbeat or lungs.”

Remote monitoring, virtual reality, and automated visits are coming

Though, the ability to listen to heartbeats and lungs from afar may come to a home near you soon. Intermountain’s ConnectCare is exploring new technologies for remote patient monitoring within its hospital network.

During the height of the pandemic, Intermountain gave newly diagnosed COVID patients mini COVID kits that included pulse oximeters and other technologies so doctors could remotely track their condition at home. The result: a 50 percent reduction in return ER visits. A $200 kit prevented what could have become a three-day, $3,000 hospital stay.

“I spend more time talking about remote monitoring than anything,” says Palakanis. She says the hospital system is exploring at least 20 other conditions where such technology could be useful—mostly in cardiac and lung disease.

Lots of data—heart rate, electrocardiograms, blood pressure, blood oxygen levels, kidney function, and more—can now be measured through remote wearables and used by doctors to manage care offsite. Recognition technologies, too, are being developed to pinpoint voice, emotion, gesture, posture—which could add to a doctor’s evaluation of a patient. And telemedicine could reduce provider workloads, cut the need for hospital or clinic space, and labor-intensive data entry. It could be helpful for post-surgical check-ins, prenatal visits, health education, and medication management.

These new technologies coincide with patients who have gotten very comfortable with virtual doctor visits, according to an October survey by healthcare IT firm DrFirst. Patients reported that during virtual doctor visits, they surfed the web, texted, played video games, sipped “quarantinis,” or drove in the car. Some didn’t even get dressed.

A little patient etiquette might be in order, but most people prefer the comfort of an online waiting room to one inside of a clinic. And that’s good news for startups like Doxy.me, because widespread adoption of the technology presents new opportunities to innovate.

With no outside investors calling the shots at Doxy.me, Welch says he feels more autonomous and free to innovate: “We’re going to create the future of what we think telemedicine should be.”